Newly Developed Porous Graphitic Carbon in U/HPLC

Article from Analytix Reporter - Issue 10

Introduction

Since the 1960s, the scientific discipline of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been dominated by silica particle-based column technologies. From irregular silica gels of the 1960s and 1970s to present-day superficially porous particles (SPPs), sub-2 µm fully porous particles (FPPs), and silica-based monoliths, the scientific literature is teeming with information on the applications of silica particle packed columns for a wide range of analyte polarities. Although there are advantages and disadvantages to each of these different particle modalities, in general, all silica-based packings have three common flaws:

- limited pH range for bonded phase stability

- limited temperature range for bonded phase stability, and

- secondary interactions from active, silanol species (though, this can be a benefit when needed to elicit resolution by ionic interactions).

Back in the early days of chromatography, liquid chromatography (LC) utilized carbon particles. However, due to the nonlinear adsorption isotherms produced by then available, active carbon particles, they were not regarded as suitable for HPLC applications.1 Through the late 1970s and 1980s, researchers optimized porous graphitic carbon (PGC) particles for less active surfaces, leading to the commercialization of carbon particle-packed HPLC. The following years saw optimization of synthetic procedures to bring down the particle size from 10 µm to 3 µm, yielding higher efficiencies in the resolution of analytes. Finally, a breakthrough, novel, synthetic process was developed over the last two years to create a smaller (2.7 µm) carbon particle with a narrower particle size distribution (PSD), higher mechanical stability, and reproducibility— resulting in improved efficiencies in the separation of challenging analytes.

Polar Retention on Porous Graphitic Carbon (PGC)

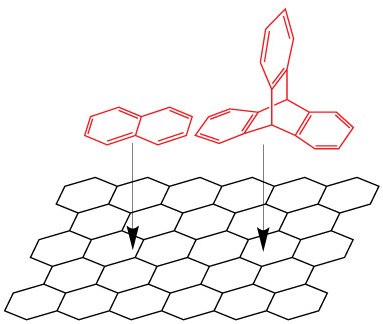

Porous graphitic carbon offers unique retention mechanisms that are beyond the scope of standard reversed phase supports. The presumption that a support made entirely of carbon atoms would behave like a perfect, non-polar phase without reactive silanol species formed the basis for PGC’s development. However, further research revealed that this was not the case. The retention properties of PGC turned out to be different from traditional non-polar phases.2 Studies by both Möckel et al. and Tanaka et al. showed mixed properties when comparing PGC to ODS (C18) phases.3,4 While comparing PGC to ODS, the researchers discovered that, in some cases, a change in substituent, regardless of its polarity, could induce an increase in retention while on the ODS column, retention decreased. The researchers believed that polarizability of the analytes and graphitic surface were at play for the results they observed. Ross and others also observed similar behavior and came up with the term PREG (Polar Retention Effect on Graphite) to explain this distinctive characteristic of PGC.1 While the exact mechanism for this phenomenon is still not clear, their explanation is still generally accepted. Those researchers surmised that the effect might be because of the uneven charge distribution in analytes due to delocalized electrons or polar functional groups and the high polarizability of the delocalized electrons of graphite. That is, when the polar analyte approaches the graphite surface, it produces an induced dipole. This interaction is heavily dependent on the polarizability of the surface, charge distribution of the analyte, and the orientation of the functional groups as they approach the graphite surface (Figure 1).

Even if the explanation for PREG is still unclear, it is obvious that PGC has special retentive properties, making it more suitable for polar compounds than standard reversed-phase approaches. Some key takeaways from PGC’s ability to retain analytes are:

- PGC will behave like the conventional ODS phases in many ways for many analytes.

- Typically, higher organic percentages must be used in the mobile phase as compared to ODS.

- Not every polar analyte will retain strongly on PGC, but PGC tends to retain polar compounds stronger than ODS phases.

- Analyte size and shape are important considerations. Planar compounds, especially aromatics, are good target analytes as the orientation can force an interaction (Figure 2 for analyte alignment example).

- Since PGC can have varying interaction strengths with analytes based on their electron distribution (size, shape, and orientation factors), it can discriminate between closely related compounds such as isomers or similar compounds with minor differences in functional groups.

Figure 1.Illustration of induced dipole-dipole interaction as analyte advances towards the graphitic plane.

Figure 2.Representation of analyte (red) alignment with the graphitic surface (black). Analytes that can align their surface area flat against the graphitic plane have a stronger Interaction and tend to retain for longer as a result. More surface area contact, attributes itself to longer retention than less surface area contact. An example illustrated here is naphthalene (left, stronger interaction) vs triptycene (right, relatively weaker interaction although one additional aromatic ring).

Analysis of Highly Polar Pesticides on PGC

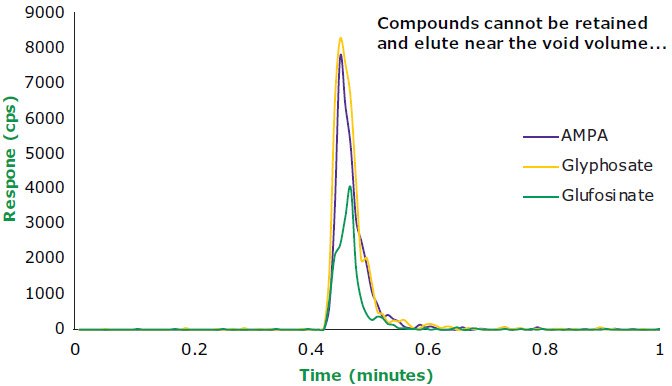

One application where PGC may be of benefit is the coelution of polar analytes of interest within the void volume of an RP column. One example of this is the analysis of challenging polar pesticides such as glyphosate and related analogues. As seen in Figure 3, the use of a conventional ODS column, in this case an Ascentis® Express C18, 5.0 cm x 3.0 mm I.D., 2.7 μm column, does not result in the retention of such compounds and coelution is observed. In this case, 95:5 water:acetonitrile was used to protect the C18 phase from potential de-wetting. However, the Supel™ Carbon LC column was able to retain four polar pesticides (aminomethylphosphonic acid, glyphosate, glufosinsate, and acetyl-n-glufosinsate) using a simple gradient with a Mass Spectrometry (MS) friendly buffer (Figure 4).

AMPA, Glyphosate, and Glufosinate retention on a 5.0 cm x 3.0 mm x 2.7 μm ODS Column in 95/5 Water:Acetonitrile

Figure 3.Three polar pesticides on an ODS stationary phase. No separation occurs and the compounds elute at or near the void volume of the column.

Four Polar Anionic Pesticides on Supel™ Carbon LC

Analysis of Paraquat and Diquat on PGC with a Simpler Gradient

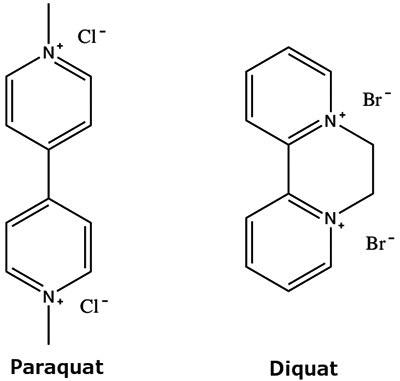

PGC may also aid in improving a pre-existing method that might be using a more complicated buffer setup. An example of this method conversion is the improvement of a hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) method for the separation of two polar herbicides, paraquat and diquat (Figure 5).

Figure 5.Analyte structures – (Left) Paraquat, (Right) Diquat.

Typically, some form of HILIC (Figure 6 & Table 2) or reversed-phase is used to retain both these compounds. The two herbicides are organic salts, highly soluble in water, and insoluble in most organic solvents. Also, both are weakly retained in reversed-phase chromatography (RPC). In addition, RPC methodology requires heavy ion-pairing to improve the interaction strength, and peak shape of the analytes. While HILIC makes sense as it is better at retaining hydrophilic species than conventional reversed-phase, it still requires aggressive buffering and the peak shapes are not ideal (Figure 6).

Figure 6.Separation of paraquat and diquat using HILIC conditions (Table 2).

Considering PGC’s ability to retain polar analytes, as well as the structure of the analytes, paraquat and diquat are easily retained without the need for an aggressive 200 mM buffer concentration. Figure 7 shows paraquat and diquat being retained using a simple gradient and 0.1% difluoroacetic acid (DFA) as a modifier (Table 3) to improve peak shape. The resolution is noticeably better, and the gradient can be adjusted for a faster analysis, when desired.

Figure 7.Paraquat/diquat separation by PGC. Better peak shape is achieved without the need for an overly concentrated buffer. In this case, DFA acts as an ion pair reagent. Elution order: 1) Paraquat -4.362 min 2) Diquat -7.295 min. (Conditions Table 3)

Analysis of Vitamin D2 and D3 Metabolites and Their Epimers

Finally, an application highlighting the necessity of PGC materials is the separation of vitamins: more specifically, Vitamin D and its metabolites. Vitamin D metabolites have been used as biomarkers for various possible disease states and vitamin deficiencies. The tests are based on the level of two metabolites in blood: 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3. It was found that these biomarkers could be further metabolized through a C3-epimerization pathway, resulting in two additional forms of metabolites, C3-epi-25 hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 (Figure 8). Also, a recent topic has centered around the epimer having the same biological function as the non-epimers. It is necessary to detect the level of the epimers among the metabolites using LC-MS. Since the epimer and its non-epimer metabolite have the same m/z ratio, it is necessary to separate the epimers from their corresponding non-epimer metabolites prior to MS detection.5-7

Figure 8.Structures of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 and their respective epimers. (A) 25-(OH)-D3 (B) 3-epi-25-(OH)-D3 (C) 25-(OH)-D2 (D) 3-epi-25-(OH)-D2

For this reason, an application is required to resolve all four of the compounds. PGC has shown to be effective at resolving both vitamin D2 and D3 as well as the epimer analogues. By utilizing a simple gradient with strong organic mobile phases (Table 4), all four compounds can be fully resolved in a reasonable analysis time (Figure 9).

Figure 9.Separation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 and their epimers on Supel™ Carbon LC. Elution order:

1) 3-epi-25-(OH)-D3 – 8.294 min;

2) 25-(OH)-D3 – 9.125 min;

3) 3-epi-25-(OH)-D2 – 11.126 min;

4) 25-(OH)-D2 – 12.062 min

Conclusion

Porous graphitic carbon is a novel stationary phase and gives the chromatographer an additional chemistry option in the separation of challenging compounds, beyond the realm of conventional silica-based reversed-phase chromatography. While in many respects, PGC may behave like a reversed-phase column, it also offers the advantages of enhanced temperature, solvent, and pH stability. Moreover, because of the unique properties of graphite, highly polar compounds (that may need HILIC or ion-exchange conditions) can be retained on a PGC column. Although its retention mechanisms are yet to be elucidated, it is clear that PGC has unique retentive properties towards polar compounds – especially planar molecules or analytes with double bond conjugation that can interact with the electron cloud of graphite. PGC is a unique stationary phase amongst more conventional HPLC stationary phases and further advancements in PGC particle design may result in even better resolving power for a wider range of compounds.

References

如要继续阅读,请登录或创建帐户。

暂无帐户?