MSI检测和IHC

MSI检测

历史

错配修复

错配修复的预后意义

结直肠癌中缺失

遗传性非息肉性结肠癌

遗传咨询和管理

预后

MSI检测

结直肠癌是大多数西方国家居民中普遍发生的疾病,仅次于肺癌。1尽管外科手术技术和化疗方案有所改进,但该疾病的预后在过去几十年中并未得到明显的改善。这些问题促使人们更加关注结直肠癌的病因和致病性。

尽管饮食因素已在病因学研究中得到了充分的研究2,但该疾病最可预测的危险因素,即遗传倾向,受到的关注有限。这可能是由于临床医生对遗传因素在癌症病因中的作用缺乏了解。3例如,许多医生认为家族性腺瘤性息肉病(FAP)是与结直肠癌病因有关的唯一遗传危险因素。然而,FAP约占结直肠癌总发病的1%,而遗传性结直肠癌综合征的发病率至少是FAP的六至八倍。3,4

遗传性非息肉性大肠直肠癌(HNPCC)或Lynch综合征是一种常染色体显性遗传综合征,占结直肠癌总发病的5%至10%。5由于缺乏特征性诊断,促使人们引入了确定该诊断的某些标准:(a)经组织学证实的结直肠癌,至少有三个亲属(其中一个是另外两个的一级亲属);(b)至少连续两代发病;(c)在50岁之前,诊断出一个或多个结直肠癌病例。这些标准被称为“阿姆斯特丹标准I”,旨在鉴定HNPCC家族是否患有遗传性结肠癌。5-7

HNPCC的典型特征包括相对年轻的结直肠癌家族史(CRC),以近端肿瘤为主,以及倾向于同时发生或异时发生的多个原发肿瘤。某些类型的结肠外肿瘤也与该疾病有关,例如子宫内膜、卵巢、胃、小肠、肝胆道、胰腺、脑和泌尿道的肿瘤。6,8-10

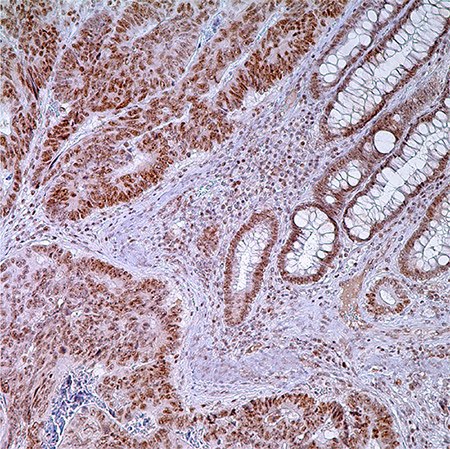

图 1.PMS2 (EPR3947†) -结肠腺癌注:固有层中腺细胞,普通隐窝细胞和淋巴细胞核酸标记。

历史

Henry T. Lynch 在咨询没有明显息肉病的有CRC病史的病人时偶然发现的,最终以他的名字命名该疾病。29,30对患者家庭的血统分析是Lynch 1966年“癌症的遗传因素”的基础。该项关于大中西部2大家族的研究成果发表在了Arch Intern Med上。17Lynch 和 Krush于1971年发布的家族更新中,包含了650多个家族成员的数据。其中提到了许多该症状的显著特征:(1)腺癌发病率增加,主要是结肠和子宫内膜;(2)多发性肿瘤风险增加(3)常染色体显性遗传以及(4)癌症早期发病。10尽管Lynch 和Krush提出了这些观点,科学界还是表示怀疑,因为当时的主流想法为环境因素是导致癌症的主要原因。29,30

图 2.遗传性非息肉病结直肠癌(HNPCC)遗传筛查建议。

Lynch的想法逐渐受到人们的关注,尤其是在国际社会,最终由“来自8个不同国家的30位顶尖专家”组成的“遗传性非息肉性结肠直肠癌国际合作组织”组织起来。该小组于1990年夏天在阿姆斯特丹会面。这次会议的主要成果是制定了一系列临床标准(现称为阿姆斯特丹标准,俗称“ 3-2-1”法则),以作为未来研究的共同起点:(1)至少3名亲属经组织学证实为结直肠癌,其中1名是其他2名的一级亲属;家族性腺瘤性息肉病应排除在外;(2)至少连续2代发病;(3)至少有1人在50岁之前诊断出癌症。19在1998年的小组会议上更新了阿姆斯特丹标准(AC),承认了结肠外肿瘤的重要性(即子宫内膜、小肠、输尿管和肾盂)。修改后的AC-II见表1。

阿姆斯特丹标准II:HNPCC家族临床标准*(表1)

- ≥3位亲属有HNPCC相关癌症**

- ≥2个连续世代受影响

- ≥1位是在50岁前确诊

- 其中1位必须是另外两位的一级亲属

- 排除家族性腺瘤息肉病

- 肿瘤必须经过病理检查确诊

Gastroenterology.1999 116:1453-1456.2.

*所有标准都必须符合。

**结直肠癌,子宫内膜,小肠,输尿管或肾盂癌症。HNPCC是指遗传性非息肉病结直肠癌。

林奇综合症的分子遗传学基础大部分在1993到1994的连续报告中有阐述。Peltomaki和同事们认为疾病(取材于2个符合原发性AC的大家族)和2p染色体上某个位点有关。随后,3个小组分别报道了CRC特异的分子表型,它的特征为长度改变的简单重复序列。三个小组分别把这一现象才称为“重复错误(RERs)”,“MSI”和“简单重复序列普遍存在的体细胞突变”。Aaltonen et al31发现11/14(79%)遗传性非息肉病结直肠癌和6/46(13%)散发性CRC中RER表型为阳性。散发性RER+肿瘤和HNPCC病例都有右侧优势和近二倍体状态。Thibodeau等人32在25/90(28%)CRC中发现MSI,这一现象和近端位置以及生存率提高有关,和杂合子丢失呈负相关。Ionov研究小组在12%CRC中都发现了广泛的简单重复序列体细胞突变,这种突变在女性中更为普遍,还和右侧位置,低分化组织学,更少的KRAS和p53突变,以及较低的肿瘤分期有关。142到了1993年末,2p,MSH2上的相关基因已经被成功克隆,林奇家族的种系突变也被找到了。33,34第二个疾病位点被发现和3p有联系。到了1994前期,在林奇家族中,发现了MLH1种系突变。35-37接着发现疾病导致的PMS2和MSH6的突变。38-40在接下来的15年间,这些知识被用来更好地理解疾病发生和表型、发展临床诊断和治疗技术。特别引人关注的是在这一阶段2个国家癌症机构(NCI)资助的小组发布了指南(“Bethesda指南”),用来辨识哪些病人能够通过林奇综合症临床测试获益。11,12修改后的Bethesda指南(BG)见表2.

错配修复

DNA复制有一定的错误率,包括错配碱基插入(比如G错配为A)以及复制过程中DNA链滑移(导致插入或缺失)。这些错配会导致点突变和移码突变。DNA MMR系统能够找出避开了DNA聚合酶矫正功能的错误。从细菌到人,这一系统都高度保守。因为单核生物中的这一系统已经被很好地研究过,所以微生物遗传学家首先发现了微卫星不稳定性(MSI)和人癌症中错配修复功能缺失(dMMR)的关联。42,43人MMR基因是按照原核生物的对应物命名的。比如,MSH2是“MutS 同系物2”(“mut”是指丧失MutS功能的细菌菌株中广义超突变型)。MMR蛋白以异二聚体形式发挥功能。MSH2-MSH6复合体能够识别错配碱基和插入/缺失的环状结构。它募集MLH1-PMS2,后者随后指导MMR系统的剩余部分。43MSH2和MLH1是各自配对的主要(必要)组分。当MSH6缺失时,MSH2可以和MSH3配对;当PMS2缺失时,MLH1可以和PMS1配对。

修订Bethesda指南:指导结直肠癌肿瘤MSI临床检测*(表2)

- CRC诊断病人年龄 <50岁

- 无论年龄大小,均存在同步性或异时性CRC或其他HNPCC相关肿瘤**

- MSI组织学确诊CRC,病人年纪<60岁

- CRC确诊Z1一级亲属有HNPCC相关肿瘤,其中一例肿瘤确诊年纪<50岁***

- CRC确诊Z2一级或二级亲属有HNPCC相关肿瘤,不考虑年纪

J Natl Cancer Inst.2004 96:261-268.3.

*符合一条即可进行临床测试。

**HNPCC相关肿瘤是指直肠,子宫内膜,胃,卵巢,胰腺,输尿管和肾盂,胆道,大脑(胶质母细胞瘤),皮肤(皮脂腺腺瘤与角化棘皮瘤)和小肠肿瘤。

***肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞、克罗恩样反应、粘液/印章环分化或髓样生长方式。CRC是指直肠癌,HNPCC,遗传性非息肉病结直肠癌,MSI,小卫星不稳定性。

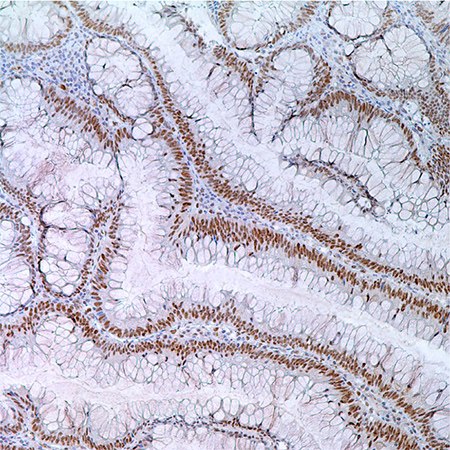

图 3.55岁男性病人结肠腺瘤中MLH1(G168-728);腺瘤细胞核酸标记。

在缺少各自主配对的情况下,MSH6和PMS2蛋白不稳定。这一点通过定量逆转录聚合酶反应和Western印迹法检测一系列dMMR细胞系可以证明。50另外,大多数林奇突变都是无义突变和移码突变,生成截短(不稳定)蛋白质;错义突变可能使生成的mRNA或蛋白质不稳定或干扰蛋白质互作。51这些MMR蛋白质特征有临床诊断效果,和MMR免疫组织化学(IHC)(临床诊断)诠释有关。

微卫星不稳定性

微卫星是简单重复的DNA序列,分散在整个基因组,有1到6个碱基单元组成,能够重复高达100次。它们在遗传上高突变,因为它们容易在DNA复制时发生链滑移。导致的环插入/缺失纠正需要DNA MMR系统行使完整功能。当MMR功能丧失,插入/缺失的环无法被修复,导致不同的微卫星延长或缩短。这一现象被称为MSI(典型凝胶条带测试MSI或测序仪峰值显示MSI)。关键位置具有简单重复序列的基因很容易发生这种情况。在对一组病例的详细研究中发现,MSI-H肿瘤中的移码突变导致肿瘤抑制因子TGFbRII,BAX,IGFRII功能丧失。更有趣的是也会导致MSH3和MSH6功能丧失。52-55因此,MSI-H肿瘤被称为增变基因表型。

1997年NCI研讨会确立了微卫星临床和研究测试参考组,确定了MSI-H,MSI-L和MSS表型诊断标准。核心参考组包含了2个单核苷酸重复(BAT25,BAT26)和3个双核苷酸重复(D5S346,D2S123,D17S250)位点。他们还提供了19个替换位点。当分析5个位点时,MSI-H在>2 个位点不稳定,MSI-L在1个位点上不稳定。鉴于有限参考组从MSS中分辨MSI-L的能力有不确定性,没有发现不稳定位点的肿瘤被称为“MSS”或“MSI-L”。当检测大于5个位点时,有40%测试位点不稳定性 >30%被称为MSI-H型,40%位点不稳定性 <30%被称为MSI-L型。562002NCI研讨会增加了一些建议,推荐对于只有一个不稳定位点的肿瘤增加额外的单核苷酸标记,因为单核苷酸标记在MSI-H型肿瘤诊断上更为可靠。12

组织学

Mecklin et al.41在1986年首次对CRC和“CFS”(癌症家族综合症)腺瘤病人进行了组织学评估,将人们对于MSI和林奇综合症遗传基础的认识提前了7年。他们发现,对比分散控制,粘液癌的发生率提高了(39%vs20%)。低分化肿瘤更为常见(24%vs12%),但是结果没有统计意义。尽管在两组中腺癌的数量相似,CFS病人的腺癌有重度不典型增生和更丰富的绒毛成分,说明它们更“晚期”。从那以后,一些肿瘤类型和组织学特征就和林奇症状和MSI-H CRC联系起来:粘液,印戒细胞和髓样癌,肿瘤浸润和瘤周淋巴细胞,克罗恩样炎症反应,低分化,肿瘤异质性,推挤性肿瘤边缘。24,26,41,57-63Greenson et al.26,62进一步强调了会出现各种粘液成分,缺少脏坏死以及MSI-H状态相关高分化肿瘤等情况。

传统上,粘液腺癌是指含有>50%粘液素的肿瘤,印戒细胞腺癌始终含有>50%印戒细胞的肿瘤。粘液腺癌的粘液素主要是细胞外,而印戒细胞含有的主要是胞浆内粘液素,通常会将细胞核挤到一边。64髓样癌有这样一系列细间胞结构特征:大的细胞形状,泡状染色质和突出核仁,层样间歇小梁生长和总体界限。肿瘤浸润性淋巴细胞(TILs)在这种肿瘤类型中尤为突出。64

TILs是指和肿瘤紧密混合在一起的淋巴样成分。它们主要是由CD3/CD8共表达细胞毒性T细胞组成[它们占主要可能是:(1)对丰富的肿瘤新抗体形成的应答。“突变表型”导致新抗体形成。(2)MSI-H肿瘤预后改善的潜在基础。]59 各种TILs计数(阈值)方法已经被报道,包括苏木精和伊红或CD3-免疫染色切片评估法。一种实用的方法是检查切片含有TIL的区域,计数5个连续的,40X视野,计算TIL/高倍视野(HPF)的平均值。使用该方法的研究获得了阳性结果, >2 TIL/HPF。62瘤周淋巴细胞是指肿瘤边缘的淋巴样带。而克罗恩样反应是由聚集在肿瘤浸润边缘的“突出”结节状淋巴组织组成,通常是在固有肌和周膜脂肪组织连接处。克罗恩样反应阳性阈值包括“2个或者更多大淋巴局部结块”“4X视野下,至少3个结节状淋巴结块”,“每个区域至少一个3淋巴结块”以及“低倍视野下(4X)至少4个结节状淋巴结块”。26,61,62,65

肿瘤通常被分为高度,中度和低度分化。世界卫生组织标准是有异质模式分化的肿瘤需要根据最高分化级别组分进行分类,郑重声明肿瘤前沿低分化(比如在肿瘤出芽处,上皮间质转化处)不足以将该肿瘤定性为低分化。64肿瘤异质性是指在一个肿瘤中同时出现一个或多个不同的生长模式。亚历山大和他的同事提供了一个粘液和髓质特征混合的肿瘤病例。65“推挤”或“扩张”的肿瘤边缘有别于“渗透”的。这一评估最好在低倍镜下进行。

临床测试

CRC dMMR功能临床测试可能有2种终点:(1)确诊林奇综合症;或者(2)确认所有MSI-H CRC。有效的dMMR功能临床测试和2个基本筛选策略有关:(1)根据临床和/或病例标准选择病人。(2)测试所有的CRC。在这种情况下,AC和BG这两个标准被用于人群评估,借此评定它们识别LS病人的能力。大致来说,AC-II标准灵敏度从40%到50%,而修订的BG标准则是90%。13-16,20-23,71需要强调的是,测试对象是很理想化的,这些芬兰研究者能够得到国家癌症登记处的数据,而其他研究者一般是“医院临床遗传学家”,使用“详细的问卷调查表”。使用BG标准的现实障碍是记录下可靠的家族癌症史是一件很复杂甚至是异想天开的事情。72

目前的临床指南所存在的问题还包括了对于小规模的家族和人群,识别的灵敏度降低,对于某些定期做结肠镜检查的人来说,他们的自然病史被改变了,标准识别的灵敏度自然也就下降了。另外显然,这些策略对于更大的MSI-H CRC人群来说没有用。LS临床标准的完善才会触发进一步的检测发展。

如果MSI-H状态的预测意义(比如和治疗相关性)能够在未知的,随机对照临床试验中被证实,那么测试所有CRC的方法作为MSI-H终点就会成为医疗标准。MSI测试被认为是表明MSI-H状态的黄金准则。

针对林奇综合症无定向种系突变测试是极其昂贵的(大约每个基因$1000)。MSI测试和MMR IHC被认为是筛选测试。73每种测试有各自的优缺点。MSI测试是基于PCR,在符合的肿瘤和正常组织中(通常是邻近非肿瘤性直肠或外周血),使用一组微卫星标记进行检测。它需要显微切割和一个分子诊断实验室。它无法指示出哪个特定基因需要突变分析,这是个明显的缺点。如果进一步检测被局限于MSI-H病例,它可能比IHC辨别LS的灵敏度要略微低一些,这是因为MSH6突变(可能出现MSI-L CRC)。74

大多数的诊断解剖病例实验室都很容易进行IHC检测。可以购买到LS相关的4个蛋白抗体(通过相关基因的种系突变)。一类不正常的结果是一个或多个肿瘤中的蛋白核免疫反应活性完全缺失。所有4个蛋白在非肿瘤组织中正常表达。因此,间质、淋巴细胞和非肿瘤性隐窝是重要的内参。抗原回收步骤是很重要的;在一项研究中,不充分的抗原回收和染色不够以及LS低特异性有关(然而高背景染色会导致低灵敏度)。98染色不够和异质染色经常发生,这可能是组织固定不均匀或其他技术因素造成的。在这些案例中,重复进行IHC可能有帮助。在林奇筛查中使用IHC的一个关键优势是它能够指导基因测试。MSH2功能丧失(因为缺失突变),MSH2和MSH6的免疫组织化学(IHC)不表达;而如果是MLH1功能丧失(因为缺失突变或启动子过度甲基化),就会出现MLH1和PMS2免疫组织化学不表达。单纯的MSH6或PMS2蛋白缺失说明对应各自基因发生了突变。

MMR IHC和MSI测试结果大部分是一致的。15,16,22,23,47,48,76-84 在一个大型研究中,联合使用MLH1和MSH2 IHC检测,检测灵敏度达到了92,3%,MSI-H肿瘤特异性检出100%(1144病例,其中302个为MSI-H)。77在参考组中MSH6和PMS2进一步提高了灵敏度,因为MSH6和PMS2突变正逐渐被发现是少数林奇病例的病因。44,45,47,48,79 IHC的一个潜在缺点是它无法检测出mRNA或蛋白的错义突变。正因为如此,Burgart预估MMR IHC检测LS的最大灵敏度是95%。83在我们的实验中,IHC分析检测出90%的LS和MSI-H CRC案例;和MSI测试检测LS的灵敏度相似。15,16,21-23,82 在缺少(缺失)MLH1蛋白质表达的肿瘤中,在进行MLH1突变分析前可能会先做另一个测试。MLH1启动子甲基化测试和/或BRAF变异测试。每一种检测都得益于MSI-H CRC发展史,就像我们之前讨论的那样。首先,甲基特异化PCR被用来确定MLH1启动子甲基化状态。甲基化是分散状态,因此MLH1种系突变分析可能并不需要。有一项重要附加说明。尽管在大多数LS病例中“第二次打击”不是杂合子丢失就是体细胞突变,极少病例会出现MLH1启动子过度甲基化。.27,28,68,85,86启动子甲基化测试比BRAF分析价格贵,因为技术上难度更高。

BRAF中的体细胞激活突变,在Ras/Raf/MAP激酶通路上,可能出现于各种人体肿瘤中,包括15%CRC病例。143

这种突变经常出现在无蒂锯齿状腺瘤和分散MSI-H CRC(大约75%)中,可以作为进化连接的证据。28,66‑69,70大多数突变都是点突变,是在密码子600位置(V600E)古氨酸被缬氨酸取代。在一项CRC研究中,60/63(95%)突变发生在V600E位置上。66因此,CRC上出现BRAF V600E说明病例是分散性的,而MLH1种系突变分析一般无法检测出这一项。检测点突变(而不是整个基因测序)使得BRAF突变分析在价格上更有吸引力($100)。73

在某些情况下,可能需要检测“潜在林奇综合症”病人的腺瘤,病人可能有明显的家族史,但是无法提供肿瘤组织用于检测。MMR IHC检测对于这类病例有足够的灵敏度且特异性高。25,87,88Halvarsson等人87报告了在26例“HNPCC”病例腺癌中,23/35(66%)出现MMR蛋白质表达丧失(其中88%被证明有种系MMR突变)。在>5mm的腺瘤中经常会出现染色缺失(88%)。19个MMR蛋白丧失的腺瘤都只有一个常规的轻度不典型增生。染色缺失模式预示每个病例中包含的有问题的基因。

这种情境下的染色缺失需要和有重叠细胞增生(SSAD)(通常被认为是分散MSI-H CRC的先兆)的无蒂锯齿状腺瘤中看到的情况区别开。89病灶的结构和染色缺失的模式是重要的考量。SSADs边缘有锯齿(LS的腺瘤几乎没有),可能说明MLH1和PMS2联合丧失(不是MSH2和/或MSH6)。而表达丧失一般被认为是晚期现象,通常是对肿瘤侵袭的应答。(然而表表达丧失在LS腺瘤中很常见,常伴有轻度不典型增生。)

有害种系突变是林奇综合症诊断的“黄金标准”。它意味着家族成员可以做相对便宜的,直接种系分析。接下来是需要考虑的几个点。一般情况下,用外周血进行突变分析,分析包括外显子和复杂基因内-外显子边界测序分析。大多数报道的致病突变是无义突变或移码突变,生成截短蛋白。错义突变更难分类。51大片段缺失可以解释20%致病突变,而且无法用常规测序手段检测出来。多重连接探针扩增技术(MLPA)能定量检测外显子分子量,可作为大片段缺失检测手段。90-93 LS突变分析中涉及成百上千个突变,非常复杂,尽管该技术一直在进步,测试灵敏度还是低于100%。在有令人信服的家族史情况下,即使无法明确地记录致病性种系突变,也不能把病人排除在合理的LS监测外。林奇综合症突变数据库是由国际胃肠道遗传性肿瘤学会建立的(前身是遗传性非息肉病结直肠癌国际协作小组)。94

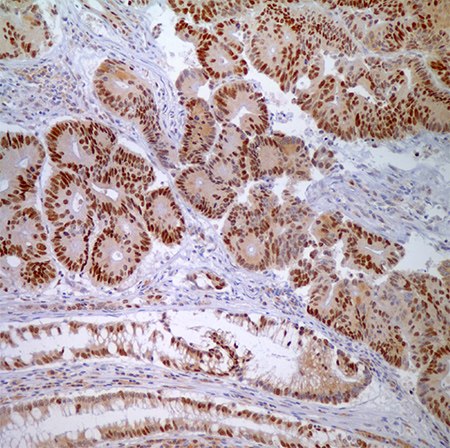

图 4.腺癌细胞与正常隐窝上皮细胞MSH6 (44)-核酸标记。

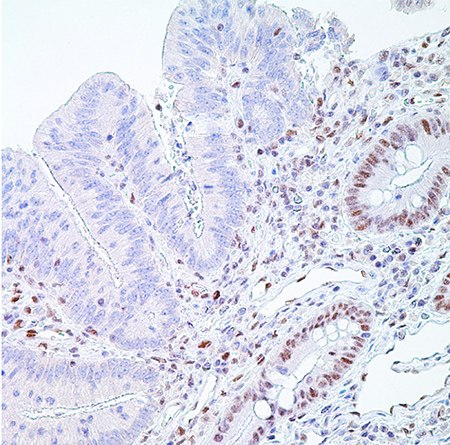

图 5.PMS2 (EPR3947†)-右边是隐窝上皮细胞(分散固有层淋巴细胞)正常核酸标记,左边是腺癌细胞核酸标记缺失,是阳性结果(MSI-H)。

直肠癌错配修复缺失预后意义

由于MMR缺失导致的肿瘤细胞选择优势是持续性的,还可能改变对于细胞凋零的敏感性。95,96,97,98 即使在早期MSI研究中,MSI-H病人比起MSS肿瘤病人生存率高。21这之后又有许多关于CRC MSI-H预后意义的研究,大多数都和早期研究结果一致,99-102这一结论尤其符合年轻病人。还有些病例没有把MSI状态作为独立的预后因子。103,104MSI状态正向预后价值体现在激活上皮内细胞毒性T淋巴细胞高分布和MSI-H肿瘤中细胞凋亡增多。99,101之前的特征可以归功于MSI-H肿瘤能够产生新的免疫原性表位(如果B2M和HLA级I位点完好,并且新的抗原存在)。这也可以解释为什么有些MSI-H肿瘤病人有很好的临床效果以及抗肿瘤免疫反应。

MSI-H的预测意义能用来挑选哪些CRC病人可以接受辅助化疗。完好的MMR系统能够识别5-氟尿嘧啶(5FU)诱导DNA损伤,105-107,导致MMR缺陷细胞对于5-Fu抗性比起对于MMR增生细胞的抗性更强。有趣的是,当MLH1甲基化时,由MLH1超甲基化导致的MMR缺陷重新获得了5-FU的敏感度。108不过,MSI-H是否能预测化疗反应还是存在争议。109-111

尽管在分子诊断实验室就能相对方便地进行MSI检测,对于临床上使用MSI-H作为分散性CRC预后标志仍存在着质疑。112,113未能达成共识的一个重要原因是,不同研究使用的微卫星标记类型和数量都不一致。一项包含了>7000个病人的大型整合分析表明MSI-H肿瘤和总体生存改善有明显关联。不过,这项研究是回顾性的,容易有各种干扰因素。LS和分散MSI-H肿瘤背后分子通路差异可能也导致了这种关联。两者分子通路差异见表1突变频率数据。将数据合在一起可能掩盖LS和MSI-H肿瘤之间的重要差异。

遗传咨询和遗传性非息肉病直肠癌处理

在确定什么时候去做遗传测试和开始监控时,就需要考虑结肠癌起始年龄和自然病史。林奇综合症的结直肠癌起始年龄比普通人群要早15到20年。10Mecklin在芬兰所做的一系列研究中119,直肠癌的起始平均年龄是41岁,年龄范围从19岁到83岁,基因外显率是89%。林奇在内布拉斯加州的系列研究中诊断年龄平均值是44.4岁。117,120大对数肿瘤发生在60岁前,年龄段高峰在40-50岁。因此,遗传检测和监控的目标年龄群应该是25-60岁。8,117大多数HNPCC病人的2个DNA错配修复基因,hMSH2或hMLH1中的一个会有突变。大于90%带有hMSH2或HMLH1的CRC病人是高频MSI(MSI-H)121,122。这些肿瘤中许多都有复制错误。144初始种系检测对于携带突变的高危人群非常合适。高危病人是指符合阿姆斯特丹标准或Bethesda指南前三条标准的病人。123有CRC的任何病人,如果自身或家族史中也有CRC或子宫内膜癌,或此病人是在50岁前被诊断出该疾病,无论是否有个人或家族病史,都符合修订版指南。

对HNPCC病人多种遗传检测策略的性价比进行比较后发现12,29,对于符合阿姆斯特丹标准的CRC病人,种系检测价格低,检测到的基因携带者最少。而对所有CRC病人进行MSI测试,价格最高,但检测到的基因携带者最多。另外,对于符合阿姆斯特丹标准的病人进行种系hMSH2/hMLH1检测,给其余的符合修订标准的病人做肿瘤MSI分析,然后给其中MSI-H肿瘤病人做种系检测,是性价比最高的策略。122如果病人符合阿姆斯特丹标准或怀疑属于HNPCC家族,首项筛选检测就应该是免疫组织化学检测hMLH1和hMSH2蛋白。123

使用石蜡包埋组织块进行的免疫组织化学检测,能够和苏木素染液共染色。当hMLH1和hMSH2表达时,细胞核染色结果阳性。使用PCR DNA分析进行微卫星分析。检测以下几个位点,比如BAT26, TGF-RII, D2S119, D3S1612, D5S404, D17S261, BAT25, D2S123, D5S346和D17S250。肿瘤DNA链和正常DNA在相邻槽比较。有2个或更多MS标志不稳定的肿瘤为MSI-H型(高不稳定),如果一个标记不稳定,则是MSI-L型(低不稳定),而没有标记不稳定则是MSS型。124如果免疫组织化学结果阳性,在检测到hMSH2或HMLH1突变后,应该进行逐个外显子测序。两个最常出现的突变类型是:始祖突变1,MLH1基因组删除,包含外显子16。以及始祖突变2,是MLH1外显子6剪切位点突变,在454-1 IVS5-1G»A。125

如果测试结果阴性,就要做MS分析。如果MS分析阴性,就不需要更多检测了。如果结果阳性,则要做MLH1和MSH2突变分析。该分析对编码外显子,包括侧翼内含子区域和启动子区域进行测序124-126(图2)。三种方法中没有一个能单独用于HNPCC遗传诊断。需要将这些方法和家族史联合起来使用。可以用Southern印迹法作为检测严重基因组重排的补充检测。如果在HNPCC家族受影响亲属中检测到种系突变时,病人终生癌症风险在80-85%之间。120分子检测过程包括标准和替代突变检测技术(表3)。

病人应该被告知HNPCC自然史,以及现有的监测和处理手段的优点。6病人必须意识到阳性结果可能在家族中产生恐慌和焦虑。HNPCC家族中的一些成员可能因为家族中多人因癌症死亡而承受难以释怀的悲痛。这些个体可能有不良的心理反应,精神科咨询可能会有帮助。120

所有这些有风险的个体应该被告知HNPCC的癌症起始年龄可能比较早,但也会有个体差异,因此相关监测应该持续终生。在HNPCC中,结直肠腺瘤会加速转化成癌症。115,121病人需要每年接受结肠镜检查,减少癌症进程发展风险。119

分子检测过程(表3)

标准突变检测技术

- 单链构象多样性

- 凝胶变性梯度分析

- DNA测序

替代突变检测技术

- 单等位基因表达分析

- Southern印迹

- 定量聚合酶链式反应

高风险HNPCC家族成员遗传咨询应该从中年开始。对于癌症起始平均年龄较早的家族,监测应该从25岁开始。因为右侧坏死占多数,完整的大肠结肠镜检查是主要的HNPCC监控手段。7,116在富有经验的医师手中,大约95%的病例能到达盲肠,穿孔率小于0.2%。10使用结肠镜还能取组织样本以及切除息肉。监测要持续到60岁。如果到那时病人还没出现症状表型表达,病人就可以按照美国癌症协会的建议,归入结直肠癌风险正常人群。内镜检查如果发现严重的粘膜发育不良或扁平腺瘤,则需要6个月后在做结肠镜复查。同步和异步的腺瘤息肉增多在林奇病例中意味着癌前病变。127对于有肠外癌症家族史的病人,包括巴氏涂片,经阴道卵巢超声波和子宫内膜穿刺活检等监测检查应该从30岁开始,每隔1到2年就做一次。泌尿系统癌症筛查应该每隔1到2年就做一次,筛查内容包括尿液分析,超声检查,膀胱镜和尿细胞学检查。对于胃和胆道食道、胃、十二指肠镜癌症筛查,肝功能检查和经腹肝胆超声也应该从30岁开始,每隔1到2年就做一次。5

当一个已知的基因携带者或有家族史的高危人群被诊断有结直肠癌时,次全结肠切除术以及回肠直肠吻合术是最佳方案,因为这些病人的异步病变的风险大。5,120,128,129当结直肠癌风险到达80-85%时,可采用预防性直肠切除术。77剩余的直肠部分每年要做内镜检查。腹部结肠切除后发展成为直肠癌的风险12年内是12%。131一个选择替代疗法是直肠结肠切除术,特别是对于hMSH2基因携带者来说更适合这个。因为他们比hMLH1携带者得直肠癌的风险更高。分段切除适合老年病人131或共病情况的病人,这些病人的预期寿命已经被先前存在的疾病降低了。132在林奇综合症II型的女性中,经阴道超声筛查是监测的最好方法。这种检查是非侵入性,对子宫内膜腔的全面检查。其他监测方法包括子宫内膜细胞取样和子宫内膜活组织检查。在林奇综合症II中,对于有可能患上子宫内膜癌的女性,在组建家庭或绝经后,可以考虑剖腹子宫切除伴随双侧卵巢,输卵管切除。5,120,127,132,133

医师应当告知病人这一遗传癌症综合症的自然史,讨论他们关于癌症的恐惧和焦虑,并且告诉他们遗传检测的好处和坏处。

预后

几个中心长期跟踪接受CRC治疗的HNPCC病人的信息结果还是令人鼓舞的。有些研究报道了结直肠癌HNPCC病人的5年生存率提高。118,119,134,135在1996年,Sankila et al.研究175例HNPCC病人,并将他们的生存状况和患有分散性结直肠癌的14,086位病人做了比较。136HNPCC的确定是基于在一个错配修复基因中发现种系突变。HNPCC病人的五年生存率是65%,而分散性案例是44%。一年后,Watson等137提供了HNPCC病人预后的更多数据。他们回顾了一组HNPCC病人并且将他们和患有分散性结直肠癌的病人做比较。他们发现在诊断后第一个10年内,HNPCC病例的死亡率几乎是分散性癌症的三分之二。最近,检测,流行病学及预后(SEER)癌症中心公布了相似的结果。患有结直肠癌的HNPCC携带者年龄调整生存率比分散性结直肠癌病人要高138,139。如果是癌症早期诊断,HNPCC病人的预期寿命比分散性病例要高三分之一。不过诊断地越晚,预期寿命越短。140

这些发现的生物学机制还不明确。有人提出HNPCC癌症更少有攻击性行为,这可能是基因组不稳定的一个意外效果。141因此,恶性肿瘤细胞的基本功能,尤其是它们的转移潜能被显著的突变负荷给抑制了。另外,基因之间,以及基因和环境间的相互作用在HNPCC自然史中也可能起到了重要作用。对于病人的系统化检测和个性化治疗也有助于在早期发现癌症,并且因此使得疾病预后有所改善。

参考文献

如要继续阅读,请登录或创建帐户。

暂无帐户?